2018 has been a year of unusual stress on global trade relationships, as sparring over tariffs, protectionism and the direction of the global economic system made headlines and contributed to market turbulence. The immediate catalyst has been the Trump administration, whose efforts to unwind “bad” trade deals and open up certain markets has led to sharp actions against multiple trading partners. However, the underlying stresses were there already, reflected in continued global trade interventions and divergent interests of various economic and geopolitical players. For many investors, the question is where all this action on trade is going and how it could affect markets and portfolios.

Our Viewpoint

- Thus far, tariffs have not had a significant impact on the economy

- Initial sharp disagreements appear to be negotiating positions

- There is a danger that protectionism could gain momentum

- Drawing autos into the trade conflict could be a game-changer

- As it stands, trade wars are unlikely to shorten the current growth cycle, and should have measured impacts on GDP growth and inflation

- Trade will likely be a source of short-term equity market price volatility through at least 2019

Action on trade has come at a rapid pace this year. After abandoning the Trans Pacific Partnership in early 2017, the U.S. announced tariffs on imported solar panels and washing machines in January 2018, followed by steel and aluminum in March, before threatening (and backing off on) new levies on autos. Europe has been in the crosshairs, as have been the country’s NAFTA partners (Canada and Mexico), and, notably, China. The U.S. president has engaged in an escalating tit-for-tat battle with China, which has resulted in the institution of a range of levies between the two countries, including on a total of $50 billion in Chinese goods through summer and close to an additional $200 billion starting in late September—initially at a 10% rate, but potentially rising to 25% on January 1, 2019. The administration has threatened another $267 billion should China retaliate, potentially covering all Chinese imports to the U.S. Shortly after the latest U.S. action, China announced tariffs on another $60 billion in U.S. goods.

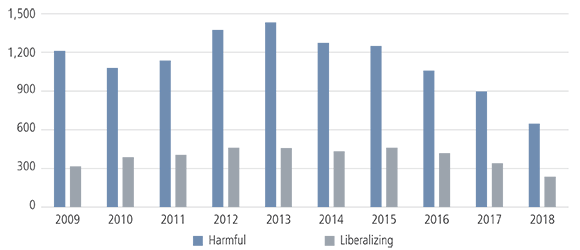

Even Before the Trump Tariffs, Globalization Was Under Stress

Number of Harmful and Liberalizing Trade Interventions Worldwide since 2009

Source: Global Trade Alert. As of September 21, 2018. Indicates trade measures that are harmful to foreign commercial interests, or that liberalize trade or make national policy more transparent.

Limited Scope…So Far

Despite the attention and related market volatility, the scope of trade actions has thus far been fairly modest in proportion to the overall economy. Exports overall account for about 13% of U.S. GDP1 (compared with 30 – 50% in some countries), and trade with China less than 1%, even with its role as the U.S.’s largest trading partner in goods. With U.S. growth apparently in the 2.5 – 3.0% range for 2018, tariffs could have a 0.2 – 0.5% negative impact on GDP going forward (with full impact unlikely this year), depending on the size and nature of the actions.

There has been some progress in ongoing trade disputes. The U.S. and Mexico reached agreement on NAFTA that will change the treaty around the edges, and as we prepared this article Canada was in negotiations to join the deal. Tempers also seem to have cooled somewhat between the U.S. and Europe over autos and other issues, while President Trump has signed a modified trade pact with South Korea. Even with recent measures, China and the U.S. continue to engage in dialogue.

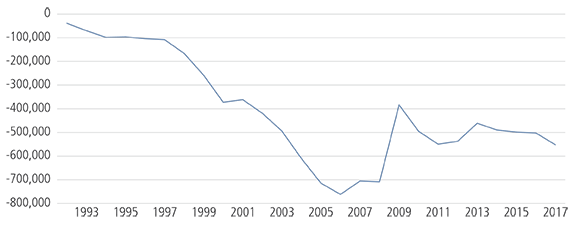

Still, despite improving after the financial crisis, the U.S. trade deficit remains stubbornly high from an optical perspective ($522 billion in 2017, or 2.7% of GDP), and fear remains that it will keep the president pushing forward and broadening the trade conflict, even in the face of considerable lobbying from business leaders and many Republicans. Thus far, there have already been a range of second-order impacts from tariffs, including a 30% spike in steel prices and Trump’s commitment of $12 billion to support U.S. soy farmers. Overall, worries remain that an acceleration of tariffs could worsen inflationary trends and put more pressure on the Fed to hike rates, as well as trim growth and earnings, potentially causing a reassessment by investors of current equity valuations. A more tense trade environment could lead to an even more volatile market.

U.S. Trade Shortfall Remains a Source of Conflict

U.S. Trade Deficit ($ Millions, Seasonally Adjusted)

Source: BEA. Data through December 2017.

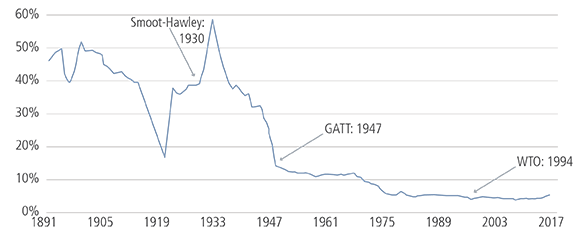

Recalling a Protectionist Past

With all this commotion, it would be easy to lose sight of the fact that tariffs and trade constraints were once a foundation of the global economic system—used to cocoon developing industries and sustain established ones. But after World War II, the world gradually moved into the modern trade era, built on multilateral tariff negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947) and later through the World Trade Organization (1994), which have reduced levies inhibiting free trade, and helped drive global growth. Countries that opened up their markets sufficiently were rewarded with “most favored nation” status (China in 2001, for example) to further allow their participation in the global economy. The tide toward openness accelerated, and in North America, NAFTA was a key agreement that in 1994 greatly facilitated cross-border trade.

With Globalization, U.S. Tariffs Have Reached Historical Lows

U.S. Duties Collection (% Dutiable Imports)

Source: BofA ML Global Research, May 2018.

Despite its contribution to global prosperity, however, there has been a well-chronicled backlash against free trade in recent years. Although income inequality has improved across countries, it has worsened within nations, and trends like offshoring, downsizing, outsourcing and the flow of cheap labor have created distinct “losers” within the economy. Recently the resentment has gained new voices, contributing to a more unsettled political landscape that has fed populist movements globally. (See our firm’s 2008 – 2018 – 2028 white paper for more on this and other major trends influencing markets.2)

This, in turn, is helping churn protectionist fervor, but it bears noting that the trade flashpoints are emerging for various specific reasons. In our view, the NAFTA situation is to some degree about political theater; steel and aluminum tariffs seem geared to preserving old-line industries; and tariffs against China are directed at protecting intellectual property and opening up markets.

A Lingering Threat

For investors, the fundamental environment of 2018 has been on a knife’s edge, between strong U.S. growth and earnings on the one hand and central bank tightening on the other. But adding to the already volatile backdrop have been fears of trade conflict, and whether public arguments and cycles of retaliation could hasten the end of the current economic cycle. Largely sentiment-driven (rather than resulting from economic news) so far, the most significant change in financial circumstances (not all due to trade conflict) has been market speculation driving up the U.S. dollar and a weakening of the Chinese yuan and stock market. It should be noted that from a trade perspective, effects on U.S. import costs may be blunted by China devaluation, although the higher dollar could make U.S. exports less attractive.

Most economists agree that a trade war would be bad news for the global economy—even for the supposed victors in any given trade spat. Tariffs, after all, take away efficiency from the marketplace and reduce potential for overall growth. Moreover, few ever seem to “get away with” imposing a tariff. Competitors either come back with tariffs of their own or find some other way to retaliate.

U.S. vs. China: Who Has the ‘Advantage’?

The U.S./China situation is telling. On its face, the U.S. seems to have more leverage, importing $500 billion in goods from China and exporting only about $130 billion. But the picture is actually more balanced. The U.S. provides about $60 billion in services to China, and multinationals operating there sold $294 billion in U.S. branded goods and $59 billion in services in 2015 (the latest date available),3 bringing the exposure of both countries to north of $500 billion.

However, there’s more to the story. As Bin Yu, Neuberger Berman’s head of China Equities, recently noted,4 while a handful of Chinese companies including domestic appliance manufacturers get 10 – 15% of their earnings from American consumers, most listed Chinese companies have very little exposure—about 5%. Moreover, U.S. imports largely reflect products made by U.S. companies in China for U.S. consumers. In effect, the Americans appear to rely more on China from an earnings perspective, rather than the other way around.

The controversy over tariffs has come at a time when China’s growth is already slowing, in large part as the country seeks to curb debt excess and focus on more quality expansion. The tariffs don’t help matters, but could provide a scapegoat for broader challenges.

Beyond retaliatory tariffs, there’s concern that China could take various measures to make life more difficult for U.S. companies operating there, or that failing such actions, Chinese consumers may veer away from U.S.-branded goods, similar to what has happened in previous political conflicts with Japan and South Korea, which reduced demand for products from those countries.

As a result, the ultimate risk of blowback from trade provocation may be more severe than might be expected at first glance. This is especially true given the integrated nature of global production. Autos, smartphones and many other goods are built across borders, and offsetting tariffs may raise their costs in unexpected ways.

What if Things Get Worse?

As we’ve said in the past,5 the major players appear to understand the stakes and seem likely to eventually find scope for agreement. Overall, the rhetoric from the Trump administration appears to reflect a negotiating strategy: make a lot of noise, seem unpredictable, but ultimately come back to the table. This is a pattern seen with Trump’s initial threats against European autos, which were followed by a friendly walk-back with the European Union president. Still, a key question for many investors is, what if the “deals” don’t come through? What if the current combative environment on trade continues or even worsens? Many on Wall Street have been working on these questions. UBS, for example, developed three scenarios from less severe (status quo, escalation) to the extreme (all-out trade war).6 Obviously, the ramifications get increasingly grim, but in the worst case (which we consider highly unlikely), they anticipated a potential reduction in global growth of 100 basis points (from 4% to 3%) with more severe impacts for the U.S. and China (each with over 200-basis-point declines). The estimated potential impact on S&P 500 earnings was a nearly 15% decline while the index was seen as potentially moving into bear territory.7

Similarly, Goldman Sachs has said that 10% U.S. tariffs on all Chinese imports could trim 3% from its 2019 S&P 500 earnings-per-share estimate, but that a broader 10% levy on all imports would curb EPS by 15%.8 Interestingly, although tariffs tend to drive up prices, our Global Investment Grade Fixed Income team anticipates only around a 0.3% boost to core inflation from current measures. With a counterweight of somewhat softer growth in the U.S. (and weakness in some emerging market economies), the impact on interest rates could be muted.

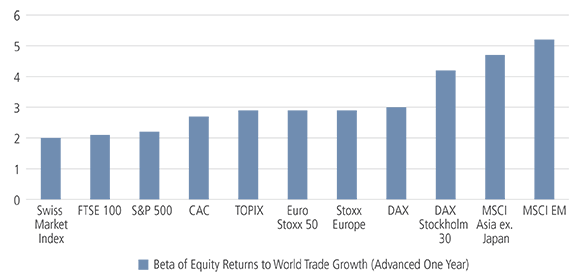

Who Gets Hurt?

From a global standpoint, some regions and countries are more sensitive to trade growth, with emerging markets and much of Asia at the top of the list (see display). The U.S. has a fairly closed economy, with a large and growing consumer sector—something it has in common with China. Based on recent equity and credit market behavior, investors seem to believe that U.S. trading partners will be the big losers from more tariffs. However, it’s misguided to think that the U.S. would be an oasis of prosperity as the rest of the world suffered. As noted, it has more vulnerabilities to China than are readily evident. And, as we learned in 2008, the global banking system is much more interconnected than it once was. Eventually, trade conflict could diminish “animal spirits” and reduce appetite for capital expenditures enough to affect growth prospects in the U.S., especially in 2019 as fiscal stimulus fades.

Exposure to Trade Risk

Some Equity Markets Likely More Affected Than Others

(Beta Since 1993)

Source: Goldman Sachs Investment Research, July 2017.

When it comes to industries and companies, given the extensive integration of global production, they may be affected in a variety of ways by accelerating trade conflict. Looking at the U.S., on the positive side, a company with purely domestic distribution may benefit when foreign competitors are penalized. On the other hand, if it uses tariffed non-U.S. inputs, its costs could rise. And if it exports to other markets, it may face retaliatory taxes on its products. Both situations may result in lower profit margins. Less directly, the imposition of tariffs along the supply chain could generally result in higher costs on a variety of goods as companies look to customers to absorb them. If customers don’t go along, that will worsen profit margins for the producer. At the macro level, higher tariff regimes could reduce growth overall, which could have a negative impact on earnings generally, but particularly to more cyclical companies.

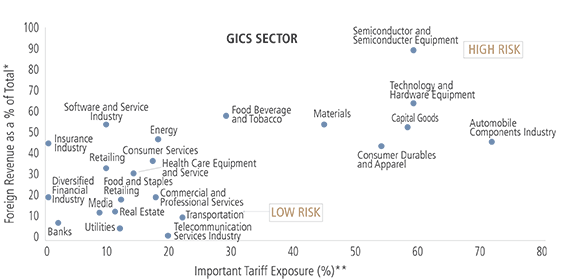

The display below shows the degree of risk to various U.S. industries of trade war with China, based on foreign revenue and import tariff exposure, with those at the upper right subject to higher risk.

U.S. Industrial Exposure to Trade War With China

*Based on top five companies in each sector by market capitalization.

**Percent of total intermediate inputs that are affected by U.S. import tariffs, based on BEA input/output (use) table.

Source: BCA Research Inc., July 27, 2018

Technology is relatively exposed, given the importance of the Chinese market both as an assembly hub and a customer as the country seeks to build out its “Made in China 2025” initiative. U.S. tariffs have largely been placed on raw materials and lower-value-add inputs rather than finished tech goods, but that could change if the trade conflict heats up. More broadly, it’s hard to find large manufacturers that are not to some degree exposed to the trade situation with China and other partners given the global nature of their businesses. Various service sectors such as financials, as well as domestically oriented business, may offer more insulation from these concerns.

Looking to Broader Factors

Clearly, trade is an issue to watch closely. Given the uncertainty around which actions will ultimately be taken, it is difficult to forecast outcomes. That said, we believe the tariffs announced thus far should have only a measured direct impact on economic growth, though that could change if conditions escalate markedly. One game-changer, in our view, would be major actions on automobiles or auto parts given the truly global and integrated nature of that business.9 Still, improvement on this and other issues suggests we may be able to avert major shocks, although trade will likely be a source of short-term market price volatility through at least 2019.

By the same token, extreme results aren't reflected in market valuations. As a result, the blowback from trade provocation ultimately may have a risk of a more severe impact than we have seen to date. The U.S. is enjoying a surge in economic activity tied to the tax cuts and a pullback in regulation, but Europe is falling behind and emerging markets are suffering from volatility over concern about global growth, trade and rising rates. It’s unclear whether the contagion could reach the U.S. Nevertheless, trade conflict could exacerbate a move toward the later stages of the economic cycle. This brings with it the need to monitor portfolios for risk, and potentially to rebalance asset allocations toward strategic targets.