There are few serious investors today who would dismiss environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks out of hand. These non-balance sheet factors have too often been the source of reputational, regulatory or legal damage, and occasionally lethal financial losses. An exhaust-emissions cheat here, an accounting scandal there, an incidence of child labor in the value chain somewhere else—these can wipe out portfolio returns and also undermine an asset manager’s reputation as a trusted fiduciary.

In developed equity markets, where data is abundant, regulatory and press scrutiny is tight, and ownership and governance structures are clear, the impact of ESG factors is well-documented and increasingly at the heart of investment processes. But application is more challenging in emerging markets, where there is greater diversity, less consensus about what constitutes best practice, less data and in many cases less transparency. In fixed income generally ESG practices are less advanced, let alone in emerging markets debt. Investors have fewer levers (they enjoy no voting rights, for example) and therefore need to influence companies or countries in more indirect ways.

Our ESG Analysis Expands from Sovereigns to Corporates

This was why we engaged with the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investments (PRI) in its call for rating agencies to incorporate ESG factors into their processes more explicitly, which resulted in its “Statement on ESG in Credit Ratings” in May this year. We ourselves began analysing ESG factors with regard to the universe of emerging markets sovereigns five years ago, as elaborated in our 2013 paper and in a recent PRI-sponsored webinar in which we presented. In the resulting model—our proprietary Country Credit Model—40% of the credit score of a given country is weighted on the basis of 15 ESG factors covering everything from energy intensity, human development and government effectiveness to political stability, rule of law, corruption levels, ease of doing business, trade openness and banking sector risk.

These things make a difference to country creditworthiness in many different ways. In a paper published earlier this year we wrote about how countries with more developed institutions can run their finances more like developed economies: Singapore’s large debt burden or Hong Kong’s deteriorating fiscal balance are less of a concern than the financial health of China or the Philippines, for example, which rests on still-developing foundations.

As well as drawing the country context that is the background to every emerging corporate, our experience in sovereigns also helped us to develop the insights, tools and data inputs that we needed to extend ESG research into corporates. We have also benefitted from work that we and our colleagues in the high-yield team have done with Sustainalytics, an investment research firm specializing in ESG, whose data complements our own analyses.

When we first engaged them back in 2014, Sustainalytics covered about half of our emerging markets corporate investment universe; on the back of the partnership we started, today they cover more than 90%. For all of those companies Sustainalytics gathers data on more than 50 specific factors in each of the environmental, social and governance groupings.

The ESG factors that apply to companies are different from those that apply to countries. Here, under the ‘E’ we capture the capacity and willingness of companies to deal in the least disruptive way with the environment within which it operates, or even to contribute to maintaining or improving it. This can be measured in terms of things such as carbon emissions targets, as well as assessments of any related incidents or controversies.

Under ‘S’ we capture the quality of the working conditions for company employees, which can capture downside risks in a company’s track record in ensuring safe working conditions and safeguarding human and employees’ rights, for example, but also the upside benefits that many studies show can come from more highly-motivated and productive workers.

Under ‘G’ we incorporate the quality of governance in managing the company and applying its standards for transparency, accountability and defining shareholder rights. In emerging markets the issue of family or state ownership can often impact the quality of governance: when equity is, in most cases, not publicly traded, this reduces the incentive to pursue best practice in the area of governance.

ESG Scores Appear to Correlate with Credit Spreads

We see evidence of a positive impact on the cost of funding when company management focuses seriously on ESG factors that affect its business. The corollary is that markets appear to demand a risk premium from borrowers with low ESG scores.

There is a midstream of companies for which ESG remains neutral for our investment case, but we allow the best performers in ESG scoring a one-notch upgrade in our internal credit rating; the worst performers can get a downgrade of up to three notches. While this would apply only to the more extreme cases, it reflects the fact that the downside from issues associated with ESG risks can be material. Clearly this implies a substantial weight for ESG in our investment risk assessment process.

Weaker ESG standards can, of course, be sector-specific: oil and gas companies will inevitably score lower on the ‘E’ parameters than, say, technology companies. For this reason it is important for investors to apply a genuine ESG-integration approach to avoid screening out entire sectors, as well as to assess whether there are some ESG risks for which adequate credit-spread compensation is available. It also underlines the importance of comparing credit spreads for companies within the same sector so that we can see past some of these sector-specific ESG characteristics.

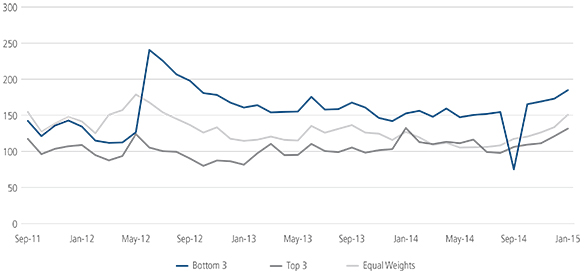

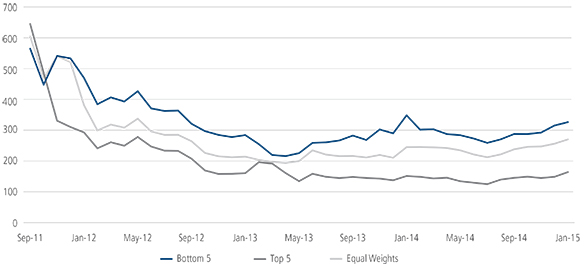

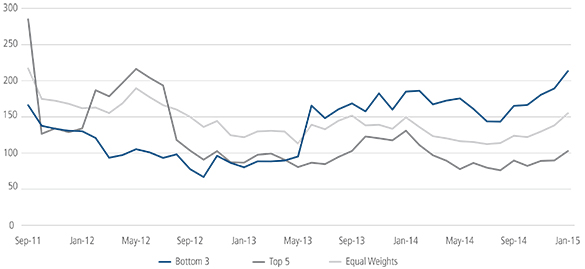

Figure 1 shows credit spread evolution over five years for the best and worst-scoring bond issuers in the real estate, consumer and technology sectors. It shows a clear correlation between our internal ESG score and the cost of funding for these businesses. The message to companies in emerging markets is simple—ignore ESG at your peril, because the premium you pay in your fixed income borrowing will reflect the risks involved.

Figure 1: ESG Scores Appear to Correlate with Issuer Credit Spreads

Credit Spreads of the Top- And Bottom-Scoring Bond Issuers on ESG Factors

TMT Sector

Real Estate Sector

Consumer Sector

Source: Bloomberg, Neuberger Berman. Average duration-adjusted spread of the top and bottom-ranked issues for each sector, ranked by our internally developed proprietary ESG scores, calculated monthly. The sudden fall and rise in the credit spreads of the bottom-three issuers in the TMT sector during 2014 occurred because a new issuer appeared with a poor ESG score but a tight spread (because of demand for its bonds from local investors); this was followed by a high-yield issuer replacing another that had improved its ESG score in the bottom-three, which took the average spread of the bottom-three back to its previous levels.

Caution is warranted when interpreting the data in these charts. There is a general correlation between poor ESG scores, wider spreads and lower agency credit ratings, all of which may, in some cases, simply reflect factors such as high leverage adding to the risk premium in the spread. Moreover, the charts also indicate that ESG-driven risk premiums can change over time. The challenge for investors and risk managers, of course, is to assess how a bond’s spread relates to ESG risks specifically.

Engagement Will Become More Important to the Process

A special focus is required with regard to emerging markets corporates that are state-owned enterprises. One of the reasons we chose to illustrate our point on risk premiums with the three sectors in figure 1 was because they include fewer state-owned companies than some others. Because their major (and sometimes only) shareholders are governments they do not face the same scrutiny as other companies and they often do not provide the same level of transparency. Some of our most important institutional clients would like to see better ESG coverage of SOEs and quasi-sovereign entities, however, because they are such an important part of the emerging markets debt universe.

This illustrates an important issue with ESG in emerging markets. While Sustainalytics covers 90% of our issuer universe, the coverage state-owned enterprises is sketchy at best. Because we are not in favour of excluding names—we see ESG analysis as a risk-management and valuation discipline rather than a method for screening-out offenders—that raises the challenge of genuine engagement with our portfolio companies’ management teams, to identify issues and try to effect improvements.

We see this as the next logical step in our progress on applying ESG in emerging markets debt, and we have already gone some way to taking it: when our team meets companies today, they are obligated to raise concerns with management if there see any ESG red flags, and to ask how these issues are going to be addressed.

In summary, the case for ESG-based analysis of portfolio companies is clear. Applying ESG research in the world of emerging markets and fixed income poses special challenges for investors, but with the help of specialists we expect our depth of knowledge and experience in these markets to enable us to develop our processes in these areas. The resulting insights will be vital for managing risks and identifying value in our markets.