At the recent Neuberger Berman ESG Investing Conference in Stockholm, Sweden, I was joined by senior decision-makers from the leading Swedish institutional investors AP1, AP3, Folksam, Länsförsäkringar and SEB, as well as Robert Eccles, Visiting Professor at the Saïd Business School and Founding Chairman of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). We discussed the range of objectives that asset owners have for ESG integration, the challenges of incomplete and non-standardized data, the growing expectation of engagement, and the opportunities fully to integrate ESG across the portfolio. The following article is based on the proceedings of the conference.

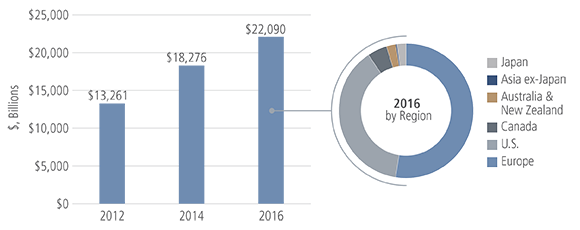

Few in our industry would deny that investing informed by Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors is now mainstream, particularly among institutional investors. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, by 2016 more than $22 trillion of assets, around a quarter of all investments globally, incorporated ESG to some extent or other. At Neuberger Berman we’ve seen significant growth in interest from our clients, too. One measure of this is the proportion of due diligence questionnaires (DDQs) that we receive from institutional clients who ask detailed questions about our approach to ESG. In 2015 only around 5% of the DDQs that we received across asset classes from North American clients asked about ESG compared to around 15% for European DDQs. In 2017 that had jumped to around 50% in both geographies.

Professor Robert Eccles of the Saïd Business School shared results from his recent survey of 582 institutional investors in partnership with State Street’s Center for Applied Research, at our recent ESG Investing Conference in Stockholm. His survey found that the most common reason why institutional investors were integrating ESG factors were because they believed it helps “foster a long-term investment mindset” and “cultivate better investment practices.”

“‘Regulatory requirements’ or ‘following the example of peers’ scored low, suggesting that this isn’t being forced on investors or some kind of fad,” as Eccles put it.

Figure 1. By 2016, ESG Assets Accounted for $22 Trillion of Investment, Globally

Assets Incorporating ESG

Source: G5IA, “Global Sustainable Investment Review” (2016).

Yet there continues to be a perception-reality gap among some investors, which is holding them back from embracing ESG. The CFA Institute’s 2017 survey asked investors who do not consider ESG factors why they did not. Common responses were “lack of demand” from clients or beneficiaries, skepticism that they add value and concern that taking ESG into account may be “inconsistent with fiduciary duty.”1

We and the institutional investors who joined us at our conference in Stockholm see lots of evidence of demand. We also think that the real-world track records of asset managers who integrate ESG present a compelling empirical challenge to the idea that these things are immaterial to performance. The claim about fiduciary duty is an old canard that has been directly countered by stewardship codes and other regulatory guidance in jurisdictions as diverse as Japan, the U.K., the European Union and the U.S.

Even the most recent U.S. Department of Labor field bulletin reiterated that the Department “recognized that there could be instances when otherwise collateral ESG issues present material business risk or opportunities to companies that company officers and directors need to manage as part of the company’s business plan and that qualified investment professionals would treat as economic considerations under generally accepted investment theories. In such situations, these ordinarily collateral issues are themselves appropriate economic considerations, and thus should be considered by a prudent fiduciary along with other relevant economic factors to evaluate the risk and return profiles of alternative investments. In other words, in these instances, the factors are more than mere tie-breakers.”2

The Department’s logic leads to the conclusion that fiduciaries who ignore financially material ESG factors when making investment decisions are potentially failing to fulfill their responsibilities as a prudent fiduciary.

Having tackled these “perceived” barriers to ESG integration, we turned the focus of our conference to four more meaningful areas of debate for sustainable investors: how to meet the varied objectives of beneficiaries for ESG integration; the perpetual challenge of ESG data; the opportunity for impact from engagement; and the potential to take a total portfolio view of impact.

How do we meet varying beneficiary objectives in integrating ESG?

Asset managers are tasked with meeting the specific investment objectives of each client. Many expect their asset manager to consider financially material ESG factors across all of their investment processes in order to maximize returns within a given risk tolerance. Others are looking for an investment process that is built of ‘best-in-class’ issuers because they believe that over the long term this will generate strong financial returns and support a more sustainable world.

This can create an awkward tension where some asset managers offer two similar strategies, one labelled “sustainable” and another which, presumably, is “unsustainable”. It can be hard to understand at what point they are meeting their fiduciary duty to consider financially material sustainability factors in their implicitly “unsustainable” strategies, but still decide an issuer is not sustainable enough to be in the “sustainable” strategy.

The institutional investors at our conference discussed the limitations of labels.

“Our end beneficiaries do not select one fund over another from our platform for its sustainable or ESG characteristics,” as Susanne Bolin Gärtner, Head of Fund Selection and ESG at Folksam, put it. “Rather, they think of Folksam as an insurance company that conducts itself in a sustainable way. Therefore, it is a big responsibility to hold a selection of funds that enable our clients to pick any one of them, knowing that it pursues a sustainable strategy.”

Some delegates suggested that the adoption of standards such as those proposed by the EU’s High-Level Expert Group (HLEG) on Sustainable Finance could help improve standardization and meaning to labels.

“Common standards and a common language we can all understand are vital, because every fund company, indeed every team within a fund company, approaches ESG in a different way,” said Karsten Marzoll, a Senior Fund Analyst in Manager Research at SEB.

Still others felt that this put an additional responsibility on institutional investors to understand the investment process in practice. Majdi Chammas, Head of External Asset Management at AP1, part of Sweden’s system of national pension buffer funds, spoke about the importance of travelling with AP1’s external managers to see their portfolio companies together. This on-the-ground view provided the most vital insights into how those managers were integrating ESG into their processes, he argued.

But he also made the point that “doing ESG” as a manager selector goes well beyond ranking firms based on quantitative assessments, and should involve working with them to develop good practice. He recalled working with a manager that performed poorly on ESG, and how that engagement resulted in substantial progress—the firm perceived so much added value from the ideas that it applied them across their entire business.

“The few hundred million dollars we invested with them influenced $70bn worth of assets under management,” Chammas reflected. “From our point of view, that is huge impact.”

Is there really a data problem or just a relevance-and-standardization problem?

It was notable that only 21% of the investors in Professor Eccles’s survey, who were all reportedly doing or planning to do ESG investing, claimed to be integrating ESG fully into their processes. Asked what the barriers were, 60% cited the lack of standards for measuring ESG performance—essentially a data issue—and 53% pointed to the lack of ESG performance data reported by companies.

Data and reporting was by far the most important topic for our speakers and delegates, too. Kristofer Dreiman, Head of Responsible Investments at the insurer Länsförsäkringar, recalled trying to compare the carbon footprints of two credit funds, and finding that, of the 300 companies in the two portfolios, only 107 reported CO2 emissions data.

At Neuberger Berman, we see a lot of disparity between types of issuers. Disclosure tends to be better in emerging markets like Brazil and South Africa, where exchanges have stricter reporting requirements, than in the U.S., for example. Public disclosure tends to be very limited for privately held companies, but those that need to finance themselves through the credit markets are often very willing to provide disclosure to us if we ask for it.

Other participants observed that there is plenty of data in the marketplace, but much of it is not financially material or decision-useful for investors. An extreme example that I often cite is an oil and gas company that published its internal price for CO2 each year in its CDP filing (the non-profit environmental data group formally known as the Carbon Disclosure Project). CDP intends this to be the assumption a company is making about CO2 pricing to ensure that its investments would still be viable were CO2 priced at that level. During my engagement with the company I asked how it had determined its CO2 price, and management stated that this was the price paid to buy extra CO2 to pump into the ground for enhanced oil recovery. Despite the implication of public disclosure of an internal price on CO2, the company was not considering the potential price of CO2 in making investment decisions at all!

Majdi Chammas, spoke for many when he set out his taxonomy of how active managers are using ESG data. He said that he still finds that a substantial number do nothing in ESG, which is a big hurdle for AP1 to invest with them. Some have started using third-party data from providers such as MSCI or Sustainalytics, but Chammas said he thought it was difficult to add value using this standardized and lagging information. He prefers to see managers and analysts do the research themselves, and ideally gathering proprietary data for full integration into investment processes.

“To beat the market you have to be different from the market,” he reasoned. “As an investor, you should think for yourself and look for a data edge yourself.”

How can we use engagement to have impact?

Properly integrating ESG into investment processes can be costly and resource intensive. That challenge was recognized at our conference, especially in the discussion of the resource-intensive qualitative versus the more mechanized quantitative approaches.

“There’s a paradox in the market at the moment,” observed Anne-Charlotte Hormgard, a Senior Manager responsible for ESG Integration at AP3. “We know that a lot of assets are going passive, but we also hear a lot about shareholder engagement. We know that fees are coming down, which means reducing costs, including the number of people employed in the industry. Engagement is labor-intensive, so these trends appear to be in tension.”

Hormgard and others at our conference argued that the way to resolve these tensions is to find some way to focus resources. Investors can do that either by engaging only with those companies whose potential social or environmental impact is more negative (and where engagement therefore promises greater positive impact); or by engaging only on issues that can be shown to have a material impact on a company’s business performance.

At Neuberger Berman we find that it usually takes multiple concerted engagements over a period of years to have impact with a company—whether we are a bondholder or a stockholder. We disclosed over 590 structured engagements through our equity investments in 2017 in our annual UN-supported Principles for Responsible Investment filing. Yet we think a focus on overall numbers does not do justice to the impact that many managers have through deep and consistent engagement. We have shared detailed case studies in our annual Proxy Voting & Engagement Report.3

Participants also discussed the importance of thinking beyond just equities for engagement. The point was made that engagement by credit and equity analysts should be conducted separately given that they often have different objectives, time horizons and views on what is financially material. Many felt that management teams would only take credit engagement seriously if it were conducted by the same credit analysts and portfolio managers who they were used to seeing make investment decisions. There was general agreement that engagement would be a growing area of focus for fixed income investors in the years to come.

How do we fully integrate ESG across the portfolio?

While much of the discussion at our conference was predicated on investing in the public equities context, many of our speakers and delegates attempt to apply ESG across asset classes, and took the opportunity to talk about their experience.

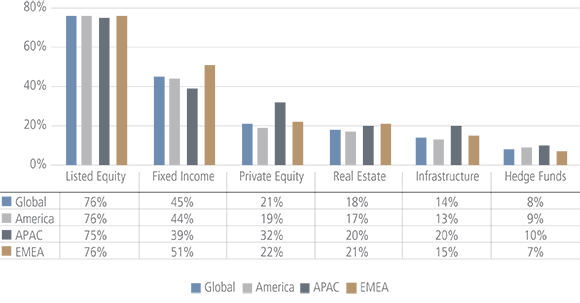

Figure 2. The Asset Classes by Region Most Commonly Integrated With ESG Analysis

Source: CFA Institute. Data as of 2017.

Responses from the 2017 CFA Institute survey indicate that ESG integration falls off considerably once we look beyond public equities, and remains almost negligible in the hedge fund sector. This was somewhat at odds with the view at our conference, however. One speaker argued that “the biggest and certainly the quickest social or environmental impact” often happens via alternative investments, and a number of delegates suggested that alternatives sometimes feel like the most natural place for ESG investing.

Innovation and new technology, as well as a long-term, highly engaged approach to company ownership, are both characteristic of private equity, for example. Infrastructure investment is financing some of the world’s biggest social and environmental needs, from care homes to wind farms. Energy and water efficiency, sustainable building materials and sustainable cities are part of the everyday conversation for real estate investors. ESG-informed investments in emerging markets with greater social, environmental and capital needs will tend to have more impact than those in developed markets.

Others suggested that when hedge funds do finally join the hunt for ESG alpha, it could constitute a major culture change for the asset management industry at large. Professor Eccles, who is on the advisory board of the JANA Impact Capital Fund, recounted how he had been approached by some activist funds that were interested in sustainable and impact investing.

“It seemed counterintuitive at first,” he said. “But the fact is, these are tough folks and they know how to change things. If the hedge fund community starts to demand changes on environmental and social issues, in addition to what they already do in corporate governance, that is potentially huge.”

While these investors are often criticized as short-termists, Eccles argued that the evidence did not support that conclusion. He also pointed out that, to further their objectives, hedge funds would need to convince the kind of institutional investor who was attending our conference to lend their votes and support, and that they were unlikely to do that in pursuit of short-term goals that might damage their own long-term returns.

“Of course there will be some greenwashing,” Eccles concluded. “But if activists and other hedge funds take this up and get support from major institutional investors, ESG issues could be powered up the boardroom agenda.”

Our own work on the concept of Total Portfolio Impact4 shows that every investment has an impact—whether positive or negative—and suggests that institutional investors consider impact alongside the more traditional risk and return metrics as they increasingly integrate ESG across their whole portfolio.

Conclusions: clarify objectives, use the data we have, engage with depth, consider total portfolio impact

Four conclusions from our conference that any institutional investor can consider:

- Be crystal clear about your ESG integration objectives: are beneficiaries looking for you to consider ESG factors in everything you do, or a range of different degrees of sustainability?

- The data challenge will never be over: active managers will always be looking for disclosure on new and emerging ESG issues. That does not mean that as an industry we should not push for standards and better disclosure, but we should all be asking, what more can we do with what we have today?

- Engagement is not about the law of large numbers: real impact comes from creating deep and lasting change whether you are a bondholder or a stockholder. Are we asking the right questions of the stewards of our capital?

- Think about the total portfolio: we need to think more creatively as we integrate ESG across the whole portfolio. How can the traditional hedge fund toolkit be used to have impact? What contribution can each portion of the portfolio make?