At the recent Neuberger Berman ESG Investing Conference in Stockholm, Sweden, I was joined by leading sustainability academic Robert Eccles. Bob is currently a Visiting Professor of Management Practice at the Saïd Business School at Oxford University. He is also the Founding Chairman of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and was one of the founders of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC).

We spoke about Bob’s research on the opportunities and challenges faced by investors who simultaneously seek to deliver market-rate financial returns and support sustainable development. We particularly focused on Bob’s work mapping financially material sustainability factors as identified by SASB to the objectives of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The following article is based on the proceedings of the conference.

Jonathan Bailey, Head of ESG Investing, Neuberger Berman

Bob, you have a great perspective on the world of sustainable investing—you have done important academic research, you’ve advised some of the most innovative ESG investment funds, and you’ve been at the heart of industry-wide efforts to enhance sustainability disclosure by corporates. Can we start by talking about your study in Management Science from 2014, which was groundbreaking in showing that more sustainable companies outperform less sustainable companies?1

Professor Robert Eccles

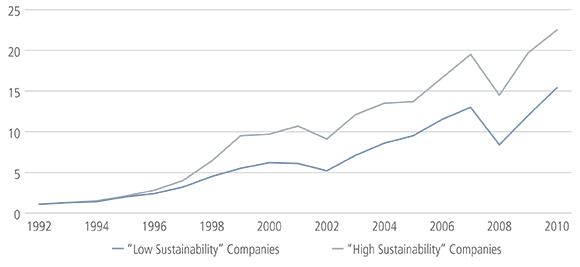

Thanks, Jonathan. It is lovely to be here in Stockholm. Yes, that paper, which I co-authored with professors George Serafeim and Ioannis Ioannou, came at an important point in the growth in sustainable investing. In the study we took a matched sample of 180 companies—90 of which had voluntarily adopted leading environmental and social practices in the early 1990s, and 90 of which had not. These practices included things like adopting energy- and water-efficiency goals, or putting in place diversity and equal opportunity policies, or promoting business ethics. The two groups were statistically identical in terms of sector membership, size, operating performance, capital structure and growth opportunities. Yet a value-weighted portfolio of “high sustainability” companies put together in 1992 generated 4.8 percentage points more of average annualized abnormal stock returns than a value-weighted portfolio of “low sustainability” companies over the following 18 years (figure 1). They also outperformed on measures like return-on-equity and return-on-assets.

Figure 1: A Portfolio of High Sustainability Companies has Outperformed

Evolution of $1 invested in the stock market in value-weighted portfolios

Source: Robert Eccles, Ioannis Ioannu, George Serafeim, “The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance” (February 2014), Management Science, Vol. 60, No. 11, pp.2835 – 2857. (Last revised February 1, 2017).

Jonathan Bailey

I remember reading an early draft and being struck by the time horizon aspect of the research.

Professor Robert Eccles

Yes, long-termism came through in several ways—the “high sustainability” companies were more likely to identify issues and stakeholders that they believed would be important for their long-term success, their executives were more likely to talk about long-term issues during conference calls with analysts, and they were more likely to attract long-term investors. But the relative outperformance of the “high sustainability” portfolio also took a long-term investment horizon—five years or more before the two groups began to diverge.

Jonathan Bailey

I think what was so powerful about the research was that it seemed to confirm the intuition that high-quality management teams are always thinking about how to position companies for the disruptions and opportunities many years out into the future, including sustainability. And of course, sustainability practices can be drivers of revenue growth or margin expansion in and of themselves. Would you agree that we’re getting to the point where most investors accept that integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investing is a fundamental part of being a good long-term investor?

Professor Robert Eccles

Yes, I think that is consistent with the evidence. I recently conducted a survey of 582 institutional investors, globally, with State Street’s Center for Applied Research. They were equally split between the three main regions, between asset owners and asset managers, and between equity and fixed income investors, and they were selected because they were already doing or planning to do ESG investing. The most favored responses to the question of why they did ESG were that it helps “foster a long-term investment mindset,” chosen by 62%, and that it helps “cultivate better investment practices.” Regulatory requirements or following the example of peers scored low, suggesting that this isn’t being forced on investors or some kind of fad.

Despite this, only 21% of the sample claimed to be integrating ESG fully into their processes. When we asked what the barriers were, 60% cited the lack of standards for measuring ESG performance—essentially a data issue—and 53% pointed to the lack of ESG performance data reported by companies. Interestingly, when we asked what the solutions might be, no one or two solutions stood out, which suggests to me that investors are still struggling with this. There is third-party data, of course, but that data is of little use without qualitative assessment—and very few respondents identified adding more ESG data vendors as a solution to ESG integration.

Jonathan Bailey

Data seems to be one of those perpetual points of disagreements. Companies say, “We already disclose a lot, yet we don’t hear sell-side analysts asking about it on quarterly earnings calls, what more do you want?” Buy-side analysts will reply, “You’re not disclosing financially material sustainability data in a decision-useful and timely fashion.”

Professor Robert Eccles

In my view, “Big Data” could be helpful. I know investors who accept that company reporting is never going to be good enough but are confident they can find other data that will tell them the real story. I have been involved with a couple of innovative ESG data firms who are trying to look at non-traditional sources of data to help investors.

Jonathan Bailey

I agree with you on the potential for non-traditional data sets. Take climate change—we get reasonably good disclosure of direct greenhouse gas emissions from large and mid-cap companies, but carbon footprinting is only part of the story. We need to combine it with data sets around climate models, physical plant locations, low-carbon transition pathways and asset depreciation schedules. We’ll continue to call on companies to disclose 2-degree scenario analysis that puts this all together, but in the meantime, we need to be piecing that puzzle together ourselves.

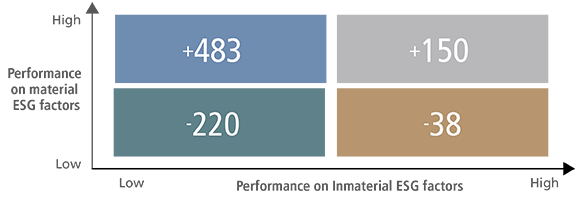

As far as standards go, we have been big advocates for the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, which you helped create, because it provides a consistent framework for companies to focus on a limited number of financially material sustainability factors specific to their industry. It also helps that your co-author on the 2014 research paper we mentioned, Professor George Serafeim, has shown elsewhere that companies that improved their performance on material, but not immaterial, sustainability factors generated 437 basis points of alpha, annualized, over two decades.2 A real-life example I noticed recently was a retail bank that had decided to go paper-neutral—committing to recycle every piece of paper they could and plant a tree for those they could not. This is a laudable goal, but as an investor I think that their sales culture, gender pay equity, employee turnover, risk management practices and data privacy practices are more likely to be material to cash flows.

Figure 2: Focusing on industry-specific Environmental and Social Factors is Key

Basis points of relative performance of top and bottom quartile companies

Source: Khan, Mozaffar and Serafeim, George and Yoon, Aaron S., “Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality” (November 9, 2016, The Accounting Review, Vol. 91, No. 6, pp. 1697 – 1724. (Last revised February 1, 2017). Performance is from April 1993 to March 2013. Study uses MSCI ESG KLD data from 1991 to 2013 at the company level to predict future accounting and shareholder performance based on ESG factors.

Professor Robert Eccles

This raises a fundamental question. On the one hand investors are increasingly convinced that bottom-up analysis of material sustainability practices at the company level can help identify the potential for alpha, but on the other hand you have the UN’s SDGs which provide a framework for making the world as a whole more sustainable. Many of us would agree that the SDGs have given us a valuable anchor for discussions about ESG: they make these sometimes-abstract concepts real for practitioners who do not specialize in ESG by laying out 17 goals. But the unit of analysis for the SDGs is the world: companies need to care about that in aggregate, for sure, but they also have to produce profits and returns. As you say, devoting effort to going paper-free may not be the best way to enhance business performance, but there’s no denying that going paper-free is good for the planet.

Figure 3: The UN Sustainable Development Goals

Source: United Nations.

Jonathan Bailey

I suppose the question is, to what extent can investors simply focus on supporting companies whose products, services, and practices integrate financially material sustainability factors, and in so doing support the achievement of the SDGs?

Professor Robert Eccles

SASB has identified the material issues that matter to investors. The SDGs are the things that matter to the world. It stands to reason, therefore, that if you want to optimize for both outcomes, you need to map the SASB material issues onto the UN SDGs to find out where the overlaps are.

There are two ways to approach this. First, you can take each of the 17 SDGs and identify how many, and which, of the 30 generic SASB material issues, like product safety or energy management, are relevant to them. That way you can see where addressing a financially material issue for you, as an investor, has a potential impact on an SDG. Research I conducted with Constanza Consolandi suggests that the biggest overlap for the SASB material issues is with SDG numbers 3 (good health and well-being), 8 (decent work and economic growth), and 12 (responsible consumption and production). By contrast, the education and marine-conservation goals do not appear to be as materially relevant to investors.3 That may suggest that the corporate sector isn’t going to make much of a contribution to those SDGs.

Turn the same lens the other way around and one can see that, in the environmental category, water, wastewater and hazardous materials management hits more SDGs than, say, greenhouse gas emissions; in social capital categories, access and affordability hits more SDGs than data security, fair marketing or human rights; and in the human capital categories, fair labor practices are relevant to more SDGs than, say, employee health and safety or compensation and benefits. Armed with that information, an investor can not only focus on the issues that are most material to its portfolio companies, but focus deeper on those material issues that contribute most to the sustainability goals.

Second, we can take that map of SASB-SDG overlaps and map that, in turn, onto industry categories. What that tells us is which industry sectors stand to have the most impact on the sustainability goals. What we found is that Healthcare, Consumption, Resource Transformation and Non-Renewable Resources are the four industry sectors that can have the most impact on the SDGs. At a very high level, therefore, investors can conclude that, if the companies in these sectors get things right in a commercially material sense for their investors, it will also have a relatively higher impact on the SDGs than getting things right in other sectors. My co-author and I plan to follow this work through by mapping the material issues in all of SASB’s 79 industries to the 169 targets of the SDGs.

How well do the SASB material issues map onto the un sustainable development goals?

| SDG | SASB General Issue Category | % of SASB Issue Mapped with the Single SDG |

|---|---|---|

| SDG #1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere. |

|

37% |

| SDG #2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. |

|

33% |

| SDG #3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. |

|

60% |

| SDG #4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all and promote lifelong learning. |

|

13% |

| SDG #5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. |

|

23% |

| SDG #6: Ensure access to water and sanitation for all. |

|

43% |

| SDG #7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. |

|

33% |

| SDG #8: Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment, and decent work for all. |

|

47% |

| SDG #9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation. |

|

30% |

| SDG #10: Reduce inequality within and among countries. |

|

33% |

| SDG #11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. |

|

33% |

| SDG #12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. |

|

50% |

| SDG #13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. |

|

30% |

| SDG #14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development. |

|

27% |

| SDG #15: Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss. |

|

40% |

| SDG #16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels. |

|

37% |

Source: Costanza Consolandi and Robert G. Eccles, “Supporting Sustainable Development Goals is Easier than You Might Think”, MIT Sloan Management Review, February 15, 2018.

Jonathan Bailey

Your research reinforces the need for governments, non-profits and philanthropists to play a big role in achieving SDGs that don’t have a significant overlap with financial materiality. We will also need to think more creatively about how investors can play a partial role through innovative financing structures like development impact bonds and blended finance. But it also raises the issue of additionality—the targets underlying the SDGs are intended to be incremental, for example reducing the rate of malaria, reducing mortality from air pollution or increasing the proportion of managerial roles held by women. That means we need companies that are addressing the SDGs to be having incremental impact beyond what they have historically done. You can’t simply ‘tag’ a pharma company as addressing SDG 3 for supporting healthy lives and leave it at that. The pharma company needs to be innovating new cost-effective malaria treatments and scaling up distribution to the world’s neediest communities, for example. If the company can do that in a way which is financially sustainable, then you get into a virtuous cycle of additional impact being generated in lock-step with additional profits for the company. That is truly sustainable impact.

Professor Robert Eccles

Yes, these are important questions. What happens when a company is performing well on material issues that contribute positively to an SDG, but doing a poor job on an immaterial issue that just happens to be important for an SDG? That isn’t going to register for a returns-focused investor. Even the SDGs themselves pose challenges. Can we achieve all 17 SDGs? Or is it necessary, and then possible, to trade off some environmental issues to achieve some social goals? That isn’t clear.

Overall, however, the SDGs and the SASB material issues have given us the first widely agreed foundation we need to analyze and shape the contribution our capital makes to the sustainability, efficiency and prosperity of our economy and our world. Impact data is the next important piece we need to start completing the puzzle.