The notion of socially responsible portfolios has been around for many decades. Indeed, at Neuberger Berman we first began excluding certain sectors and business activities in response to client requests in the 1940s. Over the last three decades we, like many investors, have evolved our approach from simply screening out sectors like tobacco or alcohol to conducting bottom-up analysis of the financially material environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks and opportunities associated with individual securities.

In the past there was a debate as to whether considering environmental, social and governance characteristics in security valuation and portfolio construction would help or hinder portfolio performance. Some investors were rightly concerned that bluntly excluding sectors might lead to a portfolio underperforming a benchmark. But, over time, real-world track records have demonstrated that, when effectively applied, bottom-up ESG analysis can in fact be a driver of attractive long-term investment performance. Importantly, this acceptance is converging with another trend: increased demand to understand the social and environmental impact of portfolios.

Many clients now have an expectation that any robust investment process will take into account material ESG characteristics. Moving past the traditional ESG “territory” of public equities, investors want to see their managers define, measure and (where applicable) enhance their ESG impact in stocks, bonds and private markets—in others words, across all components of their portfolios.

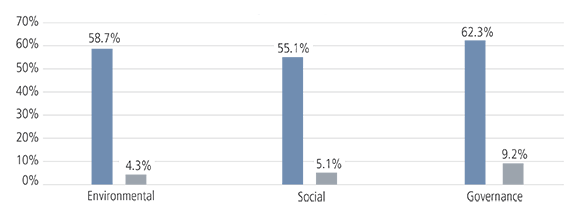

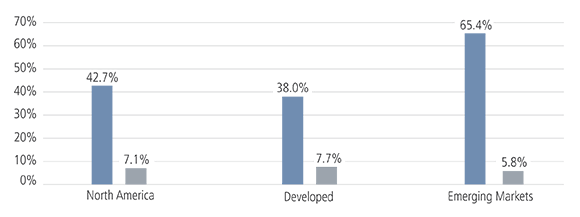

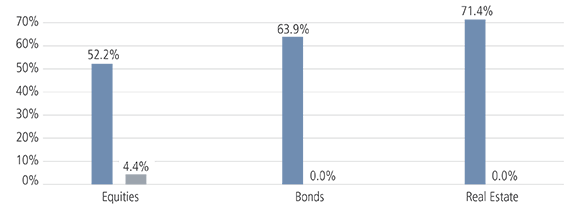

Relationship Between ESG Factors and Corporate Financial Performance

By ESG Category

By Region

By Asset Class

Represents a meta study combining the findings of at least 2,200 empirical studies on the relationship between ESG and corporate financial performance. The study aggregated 60 “review studies” using “vote-count” and meta-analysis methodologies to capture the results of underlying studies. A vote-count study counts the number of primary studies with significant positive, negative and non-significant results and “votes” the category with the highest share as the winner. A meta-analysis aggregates findings of studies econometrically, importing effect sizes and sample sizes of primary studies to compute a summary effect. “Corporate Financial Performance” encompasses a range of measures, including return on assets, return on equity, sales growth, return on sales and operating margin.

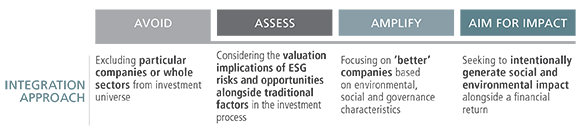

Their motivations vary. Some may seek to invest in issuers with best-in-class ESG practices because they believe this will not only lead to better investment returns, but also amplify improved social and environmental outcomes. Or they may want to address global challenges by investing in companies that seek positive change alongside investment returns. Cutting through the confusion that tends to affect nomenclature in this space, we propose the following categorization for the four different ways in which an investor can integrate ESG factors into portfolio construction:

Approaches to ESG Integration

The first category, Avoid, is fairly straightforward, representing an exclusion approach. The second, Assess, involves the careful consideration of ESG risks and opportunities as part of security valuation, and which may make a security more or less attractive relative to considering it based on more simplistic investment criteria alone. The third, Amplify, involves only investing in good corporate citizens with strong financial prospects. Finally, Aim for Impact means what it says: targeting companies that are contributing to solutions to the world’s problems, while also providing financial opportunities for investors.

Drilling Down: Asset Class Considerations

With those general categories in place, it’s important to remember that effective ESG investing relies on both broad conceptual cohesion and fine bottom-up distinctions. ESG comes into play in many different ways, and may prove to be more or less material in light of various factors, such as asset class, sector, industry and geographic location. Here are some of the variations we believe apply to asset classes:

Equities: Environmental, social and governmental factors are typically seen in light of both risk and opportunity, and most often with respect to company operations. For example, a company that properly disposes of waste is more likely to avoid unnecessary legal or regulatory liability; one that develops a diverse workforce may be better able to attract potential talent to improve productivity; and a company with strong governance standards may keep its allocation of capital on track and improve its potential for effective management decisions. Responsible corporate behavior across ESG areas can minimize risk and build reputation, while some companies may find opportunities via products or services serving customers or markets geared toward solving or ameliorating environmental or social issues.

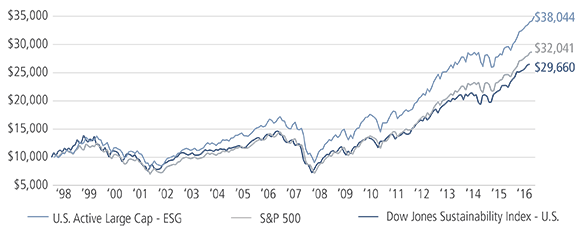

Active Large-Cap ESG Funds Have Outperformed the S&P 500

Growth of $10,000 – Since Inception of the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (January 1, 1999 – June 30, 2018)

Source: Morningstar, as of June 30, 2018.

U.S. Active Large Cap - ESG is an equally weighted net-of-fee portfolio that includes all funds that meet the following criteria: Morningstar category of Large Blend, Large Growth or Large Value and deemed socially conscious by Morningstar. The number of funds that had aggregate fund assets of at least $500 million as of June 30, 2018 included in U.S. Active Large Cap - ESG with a 10-year track record was 22 out of 42; 15-year track record was 16 out of 29 and 20-year track record was 12 out of 18.

The hypothetical analysis assumes an initial investment of $10,000 made on January 1, 1998 in the oldest share class of each respective fund equally. This analysis assumes the reinvestment of all income dividends and other distributions, if any. The analysis does not reflect the effect of taxes that would be paid on fund distributions. The analysis is based on hypothetical past performance and does not indicate future results. Given the potential fluctuation of each of the Funds’ Net Asset Value (NAV), the hypothetical market value may be less than the hypothetical initial investment at any point during the time period considered. See additional disclosures at the end of this page, which are an important part of this article. Unless otherwise indicated, returns shown reflect reinvestment of dividends and distributions. Indexes are unmanaged and are not available for direct investment. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal.Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

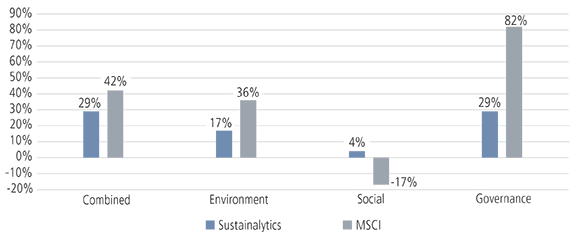

Corporate Bonds: Fixed income managers are largely focused on credit risks to principal and interest payments, rather than the upside potential that equity “owners” may enjoy. As such, ESG factors may come into play as an effective means to gauge the health of revenues, earnings and cash flows, as well as balance sheet condition. Indeed, one study compared portfolios of high and low ESG-scored U.S. investment-grade corporate credits using two well-known ESG rating systems and found that the higher-rated ESG group had a performance advantage associated with fewer downgrades (see display).

Patterns of behavior, such as loose safety conditions, may not carry an immediate penalty but point to the potential for future liability. Also certain shareholder rights, even if appealing from a governance perspective for equity investors, may be unattractive in terms of credit risk. The tenor of a credit instrument and time horizon will greatly influence the nature of ESG analysis.

Relevance of ESG Ratings to Bond Performance

Return Difference (%/year) Between Portfolios With High and Low Scores for ESG

Source: “Sustainable Investing and Bond Returns: Research study into the impact of ESG on credit portfolio performance,” Barclays, November 2016. Figures indicate the return difference between high- and low-scored portfolios as measured by ESG providers Sustainalytics and MSCI from August 2009 until April 2016. Indexes are unmanaged and are not available for direct investment. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Municipal Bonds: The municipal market includes many financings that are positive for society, and others that are neutral or negative. For example, water-sewer bonds or bonds for recycling plants could potentially help the environment and support sustainability while issuances to build sports arenas may provide a concentrated benefit to private owners instead of the broader community. Creating a portfolio oriented toward impact is particularly feasible given the relative size of the municipal market and the ability to connect to the bond use of proceeds and geographical place.

Emerging Markets: In equities, a key area of focus is governance, as many companies are controlled by governments or families. Environmental considerations may be affected by the high sector concentrations in some markets, while social criteria need to be considered in the context of both the local and global standards. Within emerging markets debt, we’ve found that ESG issues have been highly useful as a forward-looking tool for assessing the potential risks affecting sovereign debt, as well as corporate issuers.

Private Investments: ESG characteristics are an important part of due diligence relating to private equity and debt. When investing via a private equity fund or directly into a company (through a primary, secondary, co-investment or general partner stake), the track record and commitment to ESG integration on the part of general partners can be an indicator of their quality and approach to risk management and value creation.

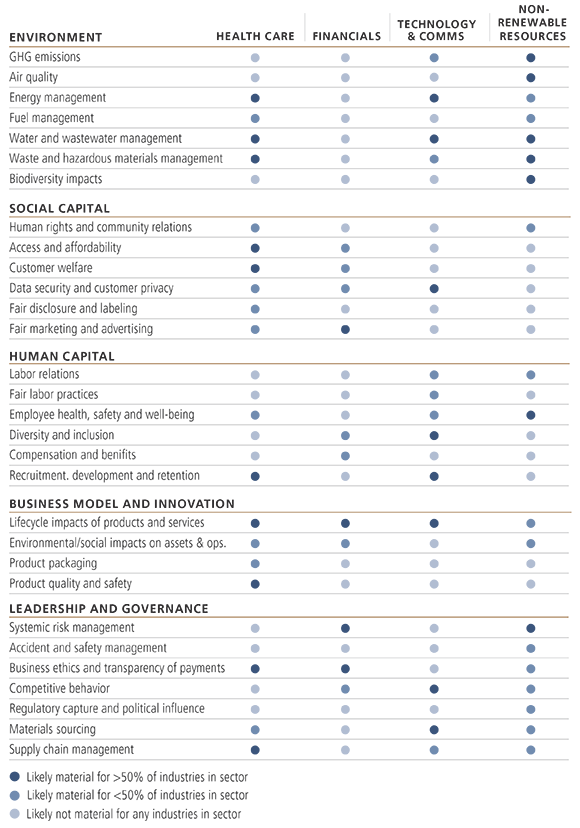

Relevance by Sector and Industry

When viewed in light of corporate sector and industry, the distinctions become more nuanced. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), a nonprofit backed by portfolio managers, developed standards for the disclosure of “material sustainability issues” specific to 79 different industries. Negative issues can pose financial risks to companies, lead to more regulation, engender criticism from investors and stakeholders or threaten brands/licenses to operate. Positive issues can involve the use of industry best practices or represent opportunities for innovation and growth. Some observations based on the groupings should not be surprising: Oil and other sectors focused on nonrenewable resources face the most environmental risk, while financials face the least. But others are more nuanced: Social issues confronting health care companies are significant, as are human capital challenges for technology companies. Consistent with other studies, material SASB factors have been found to have a substantial link with the generation of alpha (see display).

ESG Issues That Impact the Bottom Line (by Sector/Industry)

A study of large U.S. corporations from 1991 to 2013 found that companies that performed in the top quartile on material ESG issues (as defined by the SASB standards for each sector) but in the bottom quartile on immaterial ESG issues were associated with 4.8% annualized alpha after controlling for firm size, valuation, profitability and other issues. This compared to -2.2% annualized alpha for companies that performed in the bottom quartile on both material and immaterial ESG issues, and 0.5% for companies that performed in the bottom quartile on material and top quartile on immaterial ESG issues.

Source: Sustainability Accounting Standards Board Navigator. Khan, Mozafar and Serafeim, George and Yoon, Aaron S., "Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality," November 9, 2016. The Accounting Review, Vol. 91, No. 6, pp. 1697 – 1724 (last revised February 1, 2017).

Connecting the Dots

How can ESG become part of a portfolio? For investors focused exclusively on risk-adjusted return, having managers include such factors as part of the research process may be enough, and many managers already do this as part of a robust investment approach. Other investors may wish their portfolio to be tilted toward achieving certain environmental and social impacts along with favorable investment results.

The integration of “impact” need not be all or nothing. There may be practical limitations, depending on the size of a portfolio, risk profile or liquidity needs. For example, the use of a highly liquid equity or investment-grade bond strategy with an ESG orientation may be more appropriate for a retiree than a private equity fund with a long lockup period. Out of caution, investors may wish to simply take things slowly: dedicating only a sleeve of portfolios to impact-driven investing before diving in more comprehensively.

This is an exciting time for investors. ESG integration requires innovation and resources on the part of portfolio managers, and we believe those with grounding in fundamental research and a history in socially responsible and ESG investing have a decided advantage. For clients, the task is largely to stay alert, look to understand the developing landscape and seek to capitalize on opportunities where appropriate. Formerly a niche idea, the pairing of impact analysis and traditional fundamental research is gaining momentum and likely to become a major force as we move into the future.